2 Years of Gitlab Contributions at Outer Labs

Introduction

At my previous company, we used Gitlab for CI/CD and source control. I decided to extract some of my Gitlab contributions and explore them. As a way to close the chapter on my previous job, and as material for my first blog post.

Shoutout to all the people I worked with over the last two years, whether your contributions show up on Gitlab or not 🍺.

This is more of a glance at the data, and less so an evaluation of whether the data is telling me a whole lot about our team practices, velocity, extent of collaboration or lack thereof.

The data that ships with this post has been sanitized - there are no identifiers that can be tracked back to my previous company. Snapshots that appear to do so were taken prior to sanitization.

Merge Requests (MRs)

This section covers MRs authored by me only- it doesn’t include contributions I made to other’s MRs.

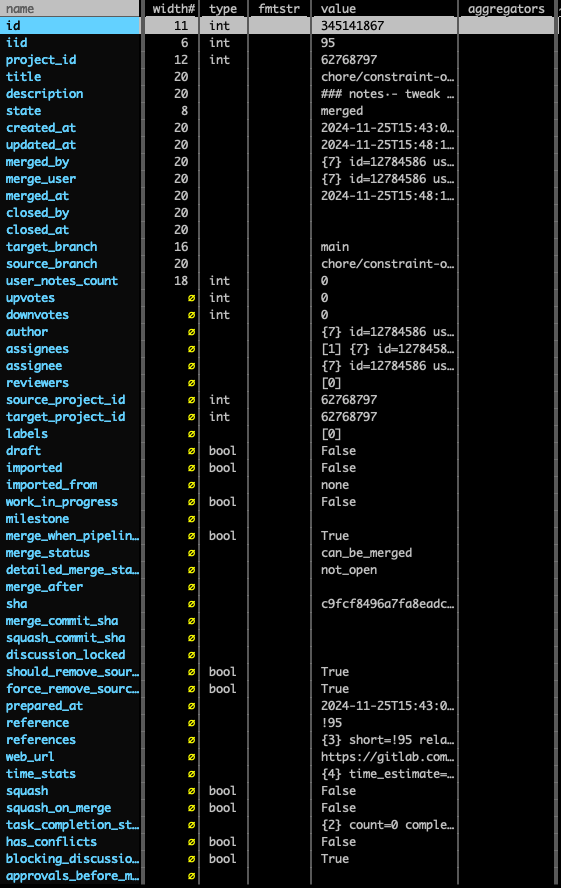

Once extracted from Gitlab via a python script, the root level properties of each MR looked like this:

Some MR Numbers

- Fix = bug fixes, hotfixes, patches, etc.

- Chore = non-feature work, like refactoring, data model changes / migrations, etc.

- Deploy = deploying to production

- Feature = new features, enhancements, etc.

- Other = everything else (likely one of the above, but cannot tell by just the MR title)

The above tries to answer what buckets of work MRs fell into roughly. This approach could have worked well if all projects would have had strict branch naming conventions and git rules to disallow wild-west branch & MR names. In reality we only had naming guards on a few projects, at a certain point in their project lifetime. An obvious way to make sense of all the MRs would have been to use labels, for tracking them by type of work, domain, or other meaningful categorization. However we stayed away from labels.

In the absence of labels, I used the MR title to pattern match and force MRs into predetermined buckets.

The pattern extracting code ended up looking like this:

const calculateMRTypeStats = () => {

const stats = {

feature: 0,

chore: 0,

fix: 0,

deploy: 0,

other: 0,

};

mrStats().mergeRequests.forEach((mr) => {

const title = mr.title.toLowerCase();

if (title.match(/^(feat|feature)/i)) stats.feature++;

else if (title.match(/deploy/i)) stats.deploy++;

else if (title.match(/^(chore|chores)/i)) stats.chore++;

else if (title.match(/^(fix|fixes|fixed|bug|patch|hotfix)/i)) stats.fix++;

else stats.other++;

});

return Object.entries(stats).map(([type, count]) => ({

route: type,

count,

}));

};

MR Duration

Interesting to think about how long MRs remain open for. I guess the duration probably has a strong correlation with the amount of back-and-forth happening. The thoroughness of reviews probably varies widely by type of company, number of engineers, bandwidth, etc. We went through periods of thorough reviews, and periods of “good enough for now”, for sure.

My approach was generally: try to keep MRs small, preferably under 10 files changed (arbitrary, and not that small, but this was “reasonably small” for me). Makes it easier to review, and reduces the risk of making careless changes. I’d like to think that is one of the reasons that 80% of MRs were opened and merged within a day or less.

MR Comments

Regarding the comment distribution on my MRs, it skews heavily toward 0 comments. I think some of the factors described above, small engineering team, solo maintainance work on legacy project, as well as 1 mo+ of experimentation phase, likely contributes to this.

MRs by Project

Joining the MRs on their associated Gitlab project ids doesn’t tell me much about the projects, but it does give me the number of projects I worked on (11), and the number of MRs per project, below:

Events

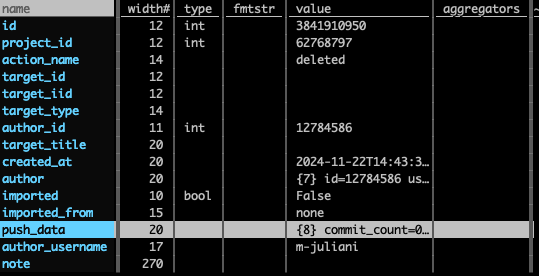

Events were part of the data extracted. Once extracted these were the root level properties:

Some of the more interesting properties to explore here are actions as well as note. Note includes who was involved in the event and thus we can look at some collaboration patterns.

Actions

Gitlab’s user-contribution events kind of describe how each of these actions are defined when you are viewing your contribution calendar. Didn’t manage to find additional documentation on what constitutes each of these actions for now.

- Pushed to = commits pushed to a branch

- Commented on = comments on a MR

- Pushed new = commits pushed to newly created branch

- Opened = opened a MR

- Accepted = Accepted suggestions on a MR (?)

- Approved = approved a MR

- Created = MR/ branch(?) seems to be more like created project given the low count

- Closed = closed a MR

- Deleted = deleted a branch (high number due to branch auto-delete after merge)

- Joined = No idea, there is only one of these, joined the org?

If you’re generous, the 2% delta between opened and approved suggests that I spent about the same amount of time/ effort creating MRs as I did reviewing them. Team sport.

See below all actions plotted between October 2022 and November 2024, in Eastern Time (ET). If you’re wondering why I seemed to start work at 5am or something: I was living in the UK and working a strange blend of GMT and ET. The sudden time shift in October 2023 to reasonable from an ET standpoint tracks with my move back to America.

Notes

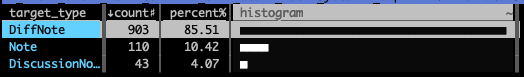

Let’s now look at the the subset of actions that have action_name equal to commented_on. This subset can have the following target_type values:

- Note = General comment on an MR

- DiffNote = Comment on an MR diff (specific line in a file)

- DiscussionNote = Comment that is part of a discussion within an MR

Not surprising: the majority of notes of are of type DiffNote (86%). DiscussionNote count is only 4%, which seems low. What’s cool about the note property is that it has properties: body (useful for extracting tagged users), and resolved_by (both of these provide collaboration information). I used this information to create the scatterplot below.

I kept @marcojuliani just to see how often I added comments, versus how often others interacted with me via commments. Black dots represent multiple collaborators on that note. If you hover over them you can see the list of collaborators.

Lastly, and just for fun - I wanted to see a heatmap of what lines were the most commented on (new lines). Each DiffNote comes with old-line/ new-line pairs, so the old lines are just context, but in this case aren’t telling us very much.

Conclusion

Nothing conclusive here. Mostly I found it interesting to see how these arbitrary slices through the data do somehow capture my time at the company over the last two years. It is imperfect and I’m sure I could have extracted other data points to tell a fuller story. (Of course it doesn’t cover very productive slack threads, beautiful FigJam flow diagrams (mostly made by others), believable Mermaid entity relationship models, and so on). A lot of the work over the last year was outside the IDE, for better or for worse.

Appendix

Context

Worth calling out that my experience with the company can be divided into these distinct chapters:

-

Client Services: Initial Onboarding (6 months) Contributing to an existing space-planning web application while learning the ropes.

-

Client Services: New Development (8 months) Development of a new space-planning web application from scratch.

-

Client Services: New development (2 months) Transitioning to a different team to work on a cost-tracking web app (tracked in a separate system, not Gitlab).

-

Transition Period (1 month) Not a lot of coding. This was a period of transition where our company went from a client services business to a startup. ENG was wearing the product hat.

-

Startup Initiatives (2 months) Working on experimental features and proof-of-concepts.

-

Product Development (6 months) Mostly building and iterating on V1 and V2 versions of our core product. In addition to this I was also doing maintenance work on a legacy project, for which I seldom had code reviews from others (at this point we were 4 engineers overall).

Data Extraction

I used a python script very similar to the one below to extract merge_requests and events. Didn’t bother with issues as we didn’t use them at all- our repositories were private and most issues were handled as issues on Linear/ Shortcut by either product or eng, and treated as regular MRs on Gitlab.

Once you create a private token on Gitlab and place it in your .env file, you should be able to run a script like this (truncated for brevity):

base_url = "https://gitlab.com/api/v4"

headers = {"PRIVATE-TOKEN": private_token}

all_contributions = {"events": []}

with httpx.Client(

timeout=httpx.Timeout(30.0, read=30.0),

headers=headers,

follow_redirects=True

) as client:

def make_request(url, params=None):

try:

response = client.get(url, params=params)

response.raise_for_status()

return response.json()

except Exception as e:

print(f"Error fetching {url}: {str(e)}")

return None

page = 1

while True:

data = make_request(

f"{base_url}/users/{user_id}/events",

params={"page": page, "per_page": 100}

)

if not data:

break

all_contributions["events"].extend(data)

page += 1

output_data = {

"exported_at": datetime.now().isoformat(),

"user_id": user_id,

"events": all_contributions["events"],

"total_events": len(all_contributions["events"])

}

Sanitization

This code below basically traverses the downloaded gitlab-activity-p.json file, and removes all unused properties and sanitizes the values (text only) for those that remain. Basically keeping the strings that we are after via regex capture groups, and removing all other text content. This reduced the size of the file by 86%.

const config = {

// properties at different levels in json tree

propertiesToKeep: [

'data',

'contributions',

'events',

'merge_requests',

//...

] as const,

patterns: {

title: [

/ac steps/i,

/(feat|feature)/i,

/deploy/i,

/(chore|chores)/i,

/(fix|fixes|fixed|bug|patch|hotfix)/i,

] as const,

description: [/ac steps/i] as const,

body: [/@[\w-]+/g] as const,

},

sanitizeOps: [

{

prop: 'title',

op: (s: string) => {

return config.patterns.title

.reduce((acc: string[], pattern) => {

const found = s.match(pattern);

return found ? [...acc, found[0].toLowerCase()] : acc;

}, [])

.join(', ');

},

},

{

prop: 'description',

op: (s: string) => {

const matches = s.match(config.patterns.description[0]) || [];

return matches.join(', ');

},

},

{

prop: 'body',

op: (s: string) => {

const matches = s.match(config.patterns.body[0]) || [];

return matches.join(', ');

},

},

] as const,

};

// recursively removes all properties not listed in propertiesToKeep

function removeProperties(obj: JsonObject): void {

if (obj === null || typeof obj !== 'object') {

return;

}

if (Array.isArray(obj)) {

obj.forEach((item) => removeProperties(item));

return;

}

const keys = Object.keys(obj);

for (const key of keys) {

if (!config.propertiesToKeep.includes(key as any)) {

delete obj[key];

} else if (obj[key] !== null && typeof obj[key] === 'object') {

removeProperties(obj[key]);

}

}

}

// recursively applies sanitization operations to matching properties

function sanitizeProperties(obj: JsonObject): void {

if (obj === null || typeof obj !== 'object') {

return;

}

if (Array.isArray(obj)) {

obj.forEach((item) => sanitizeProperties(item));

return;

}

const keys = Object.keys(obj);

for (const key of keys) {

const sanitizeOp = config.sanitizeOps.find((op) => op.prop === key);

if (sanitizeOp && typeof obj[key] === 'string') {

obj[key] = sanitizeOp.op(obj[key]);

}

if (obj[key] !== null && typeof obj[key] === 'object') {

sanitizeProperties(obj[key]);

}

}

}

// sanitizes a json file by removing sensitive properties and applying sanitization rules

export async function sanitizeJson(

filePath: string,

outputPath: string = 'sanitized.json',

): Promise<void> {

try {

const fullPath = path.resolve(filePath);

const jsonContent = await readFile(fullPath, 'utf-8');

const parsed = JSON.parse(jsonContent);

const copy = structuredClone(parsed);

removeProperties(copy);

sanitizeProperties(copy);

const sanitized = JSON.stringify(copy, null, 2);

await writeFile(outputPath, sanitized);

console.log(`Successfully sanitized: ${filePath} -> ${outputPath}`);

} catch (error) {

console.error('An unexpected error occurred:', error);

}

}

sanitizeJson('./data/gitlab-activity-p.json');